Preferred git style for code management including strategies for naming branches, committing changes, and using GitHub.

Git is a powerful and flexible version control system (VCS) for your code. There are several strategies you can employ to add, maintain, and modify your code. This doc explains my currently preferred git style and justifications for it.

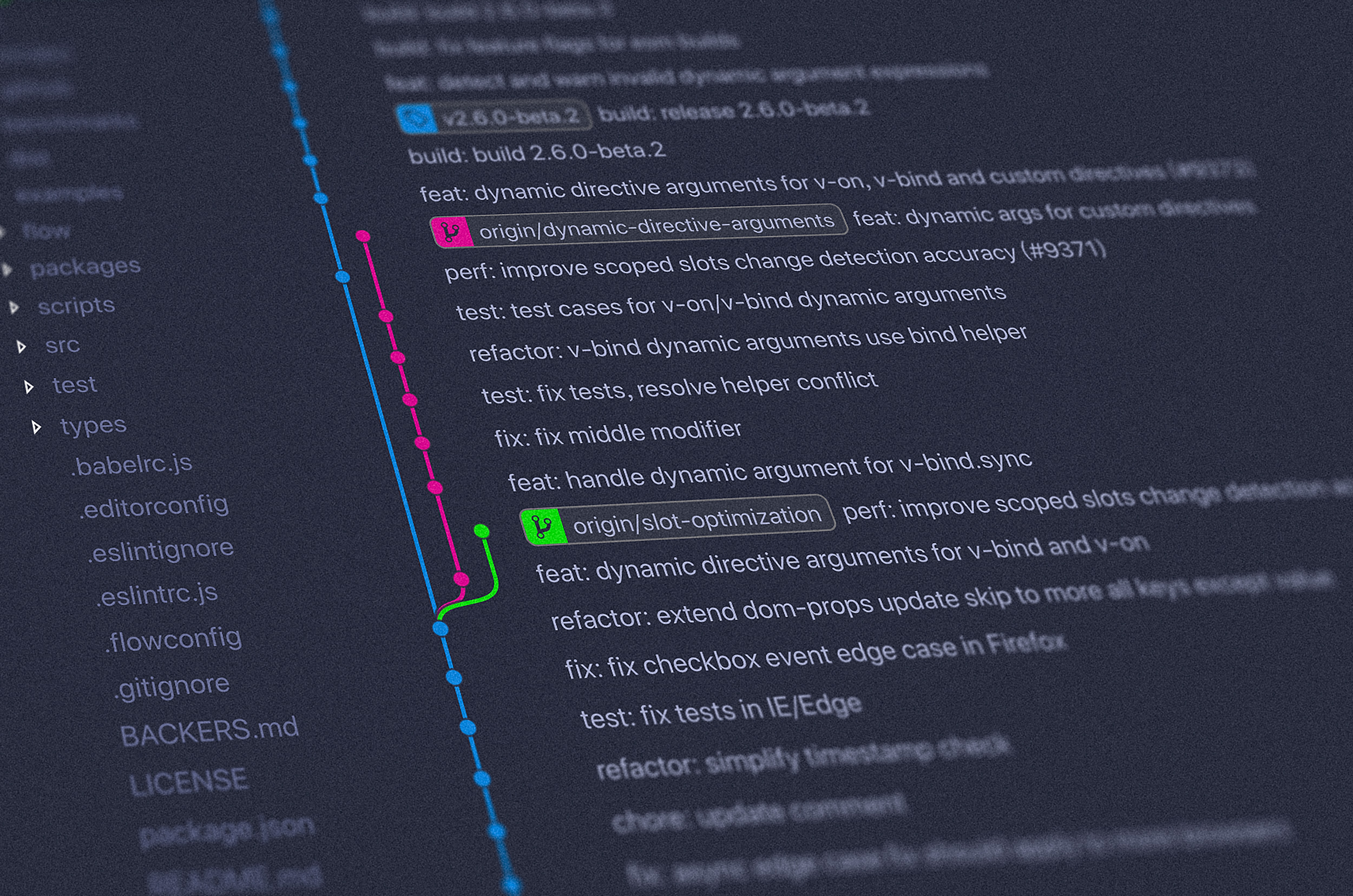

Branches

Branch naming

…or “how to name a branch”

The main branch is labeled either main or the release version.

Prefixes

Development branches are labeled <type>/<name>

where <type> is one of the following and describes the type of change being

made

- feature The addition of a new behavior, consumer effecting

- bug Fix for an issue, or something not working as intended

- upkeep Regular maintenance-like submissions. Including updates to dev facing environment and dependency updates

and <name> is a short name for what is changing.

This is similar to the git flow style which prefixes the type of change to the name of the branch “type/change”.

If you’re contributing to a large project, you should adopt a

username/type/name, which would allow you to find all of your changes easily.

Benefits:

- Compatible with automation for version bumping and changelogs. You can set up a github action to automatically label PRs with the type and then use that information to catalog changes in a release draft. This creates pretty changelog notes with relatively little additional work on your development flow.

- Keeps changes focused. If your branch has a purpose/type, it makes it more clear what should be included in a particular branch.

Characters

- All lowercase

- To separate words use

-instead of_ - Don’t use

/or\accept to separate prefixes from the name of the branch - Don’t use special characters

Examples

Add a new feature

Acceptable

feature/new-feature>althack/feature/new-feature

Unacceptable

feature/new_featureUnderscore used to separate words

Fix a bug

Acceptable

bug/fix-bug-123>althack/bug/fix-bug-123

Unacceptable

fix-bug-123missing prefix

Update dependencies

Acceptable

upkeep/new-deps

Unacceptable

upkeep\NewDeps>\and not all lowercase

Branch Management

Commit style

…or “when and how should I commit my changes”

I’ve employed two different styles of committing in my experience. I currently prefer the “google style” of “one commit, many amends” but it requires you to be a power user of git (so it is not beginner friendly).

On teams with less experience or if you anticipate needing to share your development branches across many computers, you should prefer the “many commits, one on merge strategy.

One commit, many amends (preferred)

AKA the “single commit” strategy.

This strategy employs a single commit for a single change, but you override the

commit as you develop. You can still get back history, but it’s through the less

well-known git reflog and you will need to be careful when you push since you

have to use -f.

When to commit: Make a commit for every change and overwrite your commit when you update it.

What’s in the message: A description of the change you are making. If you find you need to make more than one change, make a new commit. You will put that commit on a new branch and create a separate PR for it.

How to sync: When you sync you’ll want to use

git fetch; git rebase origin/main so that your commit is on top.

When you merge: You can employ any style when you merge since it’s a single commit. I still prefer “squash merge”.

Pros:

- Single commits are easier to cherry-pick, move, and rebase

- It is easier to see what you are working on from the log since it’s always at the top.

- Dev branches look more like

main.

Cons:

- Rewrites history (locally)

- Harder to share with other people since it rewrites history

This method is most like the method employed at Alphabet (aka Google). Since

there isn’t a need to track “history” outside of the web-based IDE, the utility

of “many commits” is diminished. It’s also not common for developers to share

their work with many others until after it has been merged into main. Neither

is it necessary for them to share code between multiple computers since the

developer space is hosted on a centralized server.

Many commits, squash merge (alternative)

AKA the “squash merge” strategy.

When do you commit: All of the time for everything. Basically, you use “git commit” as a “save” function, with the added benefit that you’ll be able to undo your saves across computers and people.

What’s in the message: It doesn’t matter. Put whatever you think is relevant to you. This is only for your reference in case you want to undo it later. You’ll be overwriting this later so this message is just for you.

How to sync: Just use the standard git fetch; git merge origin/main to update

your dev branch.

When you merge: Always use the “squash merge” strategy. This will squash all of your “wip” commits into one, using the title and description of your PR.

Pros:

- Clean

mainbranch - each PR is squashed into one commit - No need to use

-for force anything during development. - Easier sharing between computers because the history of your branch is never overwritten

- Easier to undo changes because history is never overwritten

- Easier for newbies to git to understand and employ. Bonus points for “squash merge” as a default setting in your github repo.

- If you need to sync with

main, use ‘merge’ instead of ‘rebase’

Cons:

- Harder to rebase on top of

mainif you’re trying to keep up-to-date - Merging with

mainmay make it harder to see what you’ve changed in the log since your commits could be buried

This has historically been my go-to strategy for changes due to the ability to

undo and share between machines. It is the most friendly to newbies to git. This

strategy allows you to make all sorts of changes without ever having to use -f

, which can be very dangerous (re-writing history) if you don’t know what you’re

doing.

The great part about this strategy is that it allows you to still have atomical,

“single commits” in main (through squash-merge) without risking any loss of

history on your development branch.

PR Style

Subject line

The subject of a PR should be a short summary of what is being done by the pull request. This is what will appear in your git history, so it should be informative but concise.

Try to keep your first line short, focused, and to the point.

Write in an imperative tone. Example

Add a versioning feature to the FooBar application

Instead of

Adding a versioning feature to the FooBar application

Body

This is a longer description of your pull request. It should cover details on what problem is being solved, why this is a good solution, and adds more context about the implementation.

Example:

Fixes #24

Documentation and version mismatch is now handled using versioning. Documentation will be published with a version number matching the package allowing users to find the applicable documentation for their version.

Order of operations:

1. Devs make changes

2. Version bump

3. Package released

4. New docs uploaded to the version folder

5. Pointer to latest documentation updated

PR merge strategy

Prefer squash merge strategy.

This will create a single commit for your change and merge it on top of HEAD.

Squash merge

This will combine multiple commits into a single commit before adding it to the

main branch. This will guarantee that a single pull request will result in a

single commit in your history.

Rebase-merge

This will rebase your branch on top of the latest version of the main branch

before merge. This will also create a linear history, however, this strategy can

be more complicated and may require more effort to resolve conflicts.

One advantage of rebase-merge is that all of the commits in your PR will be kept

(but placed on top of your main branch). This allows for multiple commits to

be merged while also guaranteeing linear history.

I tend to prefer squash-merge over rebase-merge as it forces PRs to be smaller and more targeted (thus keeping the PR small).